[Author’s note: At Mr. Bracq’s suggestion, I’m writing this article to a background mix of Miles Davis, Bill Evans, George Gershwin, and a host of other classical and jazz music easily downloaded from the internet. Copyright laws and my limited internetting abilities preclude me from including a soundtrack , so my suggestion for you is to hum “Rhapsody in Blue” while you read for a true 3D experience.]

I first met Paul Bracq in 2004,again in 2006, and have corresponded with him off and on over the years. Fair warning: this piece focuses mostly on his Mercedes work, in light of the 60th anniversaries of the Grand 600 and Pagoda, in honor of Paul’s 90th birthday next month, and because I’m the resident Mercedes guy in these parts.

On the cusp of turning 90, Paul Bracq is a happy man. Not because he has wealth beyond the dreams of Avarice, nor because he spends his retirement travelling in first-class style. No, it’s much simpler than that. Bracq’s philosophy is simple: “For a man to be happy takes three things – to have a son, plant a tree, and write a book – and I’ve got two books!” Add to that his lovely wife Alice, and you start to get a picture of what this guy is all about. Here is a gentleman with a genuine passion for all of the elements in his life – love, family, work, and living.

Centered in his passion is Bracq’s art – cars, paintings, and sculptures. Asking him to choose his favorite design “is like asking me to choose from among my children!” Bracq has a portfolio that even the most accomplished artist would envy, and his work ranges from the car designs that we all recognize to abstract sculpture to classic paint on canvas art – though he insists that Alice is a far superior portrait artist.

“Influences come from all around – trees are wonderful for abstract design. Or the woman’s body – perfect from every angle. When I paint abstract I like to listen to classic jazz – Bill Evans or Miles Davis – for designing cars I need something more classical – like Brahms.” Bracq also takes inspiration from the “American renaissance” cars of the 1930’s. Cars like the V16 Cadillac and the work of legendary designer Harley Earl. Even today, you’re as likely as not to cross paths with a classic Bracq design – be it Mercedes, BMW, or something else entirely – especially in Europe.

Natural Talent

Paul Bracq was born in 1933 in Bordeaux, France, son of a travelling salesman in the mortuary trade. His brothers took over the family business, while Paul was the creative one – an artist from a tender age. “Sculpture is essential to managing three-dimensional control, and even as a young child I was carving from blocks of wood.”

As he grew, Bracq’s skills inevitably improved. He was forever sculpting cars of his own design and building models of cars, boats, and airplanes, all the while studying the intricate forms of each. At seventeen, having received praise for his work from local artisans, Paul entered the Boulle School of Design in Paris. He spent three years at Boulle, honing his skills and perfecting his technique. In 1953 he was awarded first prize in the school’s competition for sculpture in wood. That same year he was recognized by the Chambre Syndicale de la Carrosserie, an automotive coachbuilders association, for his full-sized automotive renderings.

Paul eventually became an assistant to French car designer Philippe Charbonneaux, with whom he worked very closely on the Pegaso Coupé and the Franay Citroën presidential limousine. And then everything was placed on hold in 1954 when he joined the Army.

A Frenchman in King Wilfert’s Court

During his service, Paul was conveniently stationed in Germany with the French Army – Aerial Division, where he “spent all my free time on design.” It only seemed logical for him to take his designs ‘round to the good folks at Mercedes-Benz, which, even in the mid-1950s, was reputed to be the best automobile company in Europe. His designs impressed the right people at Mercedes, notably Fritz Nallinger and Karl Wilfert who offered him a job in 1956 and agreed to wait a full year for him to complete his military service. In 1957, Paul Bracq went to work in Stuttgart.

His diligence paid off, and Paul was named Chief of Advanced Design Studios with Mercedes-Benz. He recalls with a laugh that “I was the first Frenchman hired at Mercedes after the war. The Germans were surprised that a Frenchman was so hard working!” He knew the importance of his work, and the result was many long hours – sometimes working in the studios from 6:00 a.m. until 3:00 a.m., and back again after only a few hours rest.

Among his early jobs with Mercedes was designing an updated hard top for the 190SL roadster. Looking at that design today, the influence of fifties American cars is obvious, and you can see similarities in what ultimately became the W111/112 coupés. Bracq designed the original W111/112 coupé in the late 1950s, at which time management flatly rejected it. Instead, Mercedes-Benz took the uncharacteristic step of following current fashion and added fins to their saloons – a move they would regret before too long.

The coupé design, which softened the contemporary saloon’s outdated fins while preserving other styling elements, was ultimately accepted into production in 1961 as both coupé and cabriolet. The W111/112 design is perhaps the ultimate incarnation of Bracq’s personal guiding principle: “To design a timeless, good-looking car that will be successful as a used car in five years and as a concours winner in 25 years.” His beautiful W111/112 influenced the look of Mercedes-Benz cars for the ensuing ten years, but the best was yet to come.

Enter the Pagoda

Paul Bracq is generally credited as the designer behind the W113 230SL, and he was largely responsible for the car and its distinctive roof. However, Bracq insists that the car was a team effort, driven heavily by the engineering department. In fact, the car represented some significant advances in safety and structural rigidity as well as drivability. Originally conceived as a successor to the 190SL, the W113 was truly a worthy successor to the entire SL line – 190’s and 300’s.

Oddly enough, the famous roofline was inspired by a concept utility vehicle – which looked the same coming and going – which Paul had seen years earlier. With its wide track and light chassis, in many ways the W113 looks and feels much more modern than its W107 successor. Eyeing a Pagoda today, Bracq points out that “that car is still as attractive today as when it was new!”

Sedan Fever

The design brief for the Grosser 600 was simple – stately. The car was intended to appeal especially to dignitaries, heads of state, and the top elite. “Nallinger wanted short overhangs so the car would be easy to maneuver in New York City.” The Vatican was also a key customer, and eventually ordered six 600’s. With a sheepish grin, Bracq says “I hope I get into heaven for that one.”

For his S-class sedans, Bracq retained the tall windows of his classic coupé, further softening the tail to remove any trace of the 1950’s lapse-in-judgment tail fins. He preserved the traditional upright grille, but with an eye toward the future. However, Wilfert, who incidentally held a patent on the vertical headlights, insisted that the existing headlight design be retained. The result was a quintessential piece of classic conservatism.

Bracq’s classic and unmistakable W108/109 combined with his W113 to produce what became Mercedes’ best-selling car to date: the W114/115 coupé and saloon. The coupé had the familiar rear-window and roof trim of the W113 coupled with the pillarless design from the W111/112 coupés. The sedan resembled a 7/8 scale version of its big brother with its vertical headlamps and tall greenhouse. The car was an affordable entry to Mercedes style, but still built on the foundations of style, elegance, and engineered safety.

The W114/115 coupé was Bracq’s last project with Mercedes-Benz. By 1967, his designs were too modern for the conservative image that Mercedes wanted to convey – “I wanted to move too fast for them, but I left it in Sacco’s capable hands.” Still, it was not an easy decision for Bracq – he had developed very close ties to his colleagues, Karl Wilfert in particular, who “lost a son” when Bracq left. Although they remained close, Wilfert was furious that Bracq waited until he was at BMW to pen the innovative BMW Turbo, which laid the groundwork for a host of innovative technology that directly competed for the same public recognition as Mercedes’ C111 testbed.

Moving on

After leaving Mercedes, Paul spent three years working with Carrosserie Brissonau & Lotz. Projects there included the French TGV high-speed train, for which the French government felt very strongly that the designer should be French. He also designed concepts based on the BMW 1600TI and the SIMCA 1100. Unfortunately, coachbuilder wages at the time were barely enough to sustain the Bracq family, and Paul watched out for the right opportunity.

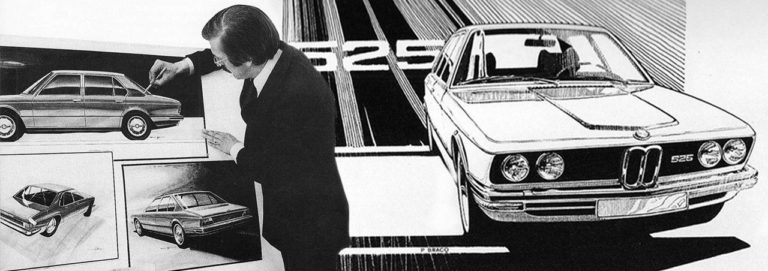

In 1970 that opportunity came along when Paul was appointed Director of Design at BMW. During his tenure, he was responsible for some of the most significant designs to come out of the Münich firm – specifically, the original three, five, six, and seven-series cars, not to mention the aforementioned BMW Turbo, which received the prestigious “Concept Car of the Year” award from Revue Automobile Suisse.

After BMW, the Bracqs returned to France, and Paul accepted a position as Chief of Interior Design with Peugeot. He worked on the 305, 505, 205, 405, and 106, as well as a number of special projects including personal transport for the Pope and numerous concept cars. He retired from Peugeot in 1996, although he hardly stopped working.

Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow

“I’m still a Mercedes designer” says Paul, handing me a small portfolio of his more recent sketches. “The difference now, is that I can say ‘no, sir!’ and I don’t have to worry about losing my job.” Indeed, his recent sketches include a number of modern renderings of Bracq’s vision of what a new Mercedes should be. He’s even got his own vision of what the Maybach could have been. I guess if you’re Paul Bracq, it’s easy to judge.

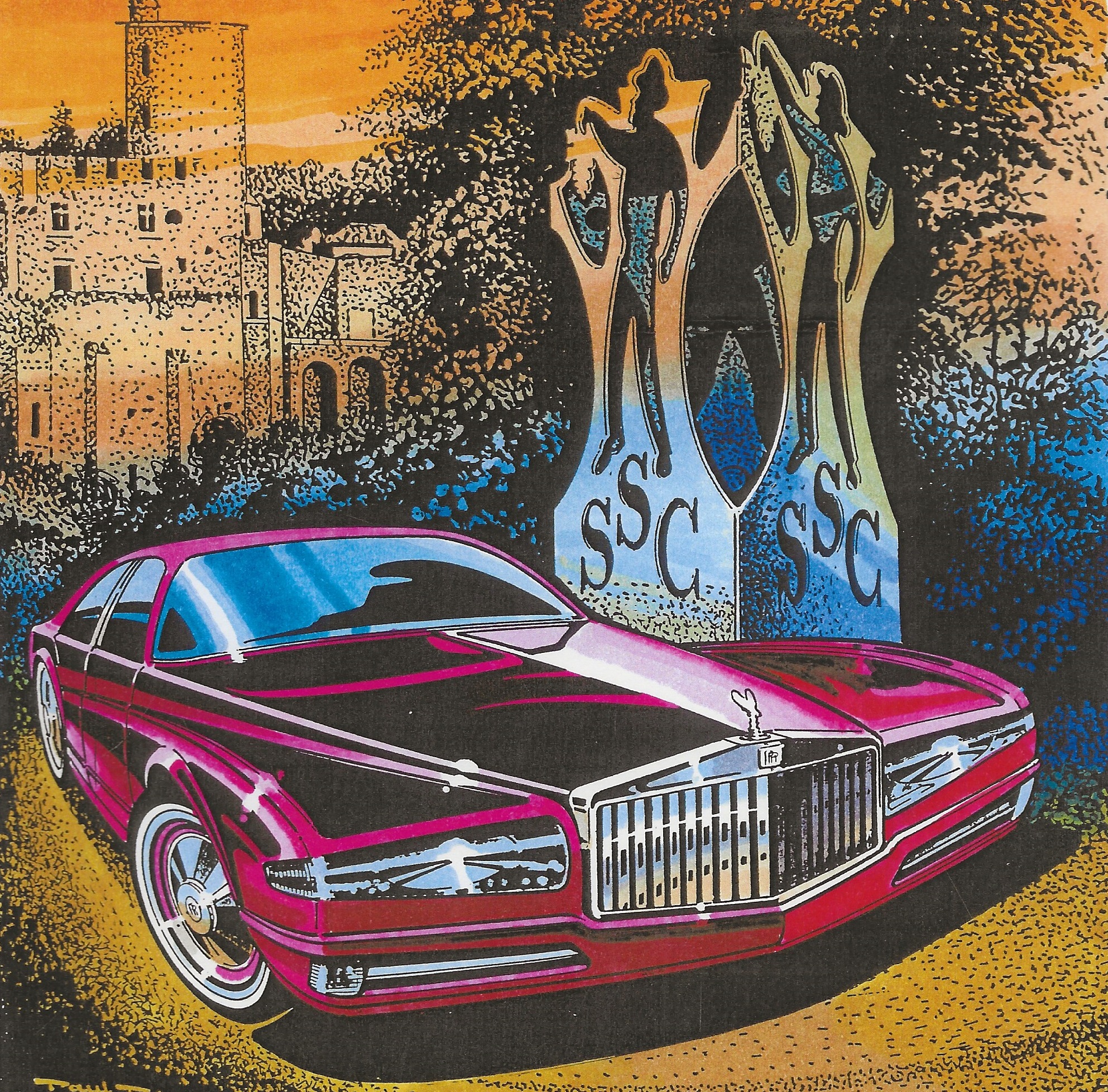

These days you can find Paul at home in Bordeaux, France, where he is most likely painting or sculpting, either for pleasure or on commission. Paul has designed concepts for a new Rolls Royce – far more attractive, I might add, than some of what BMW, er, Rolls Royce has brought to market. “I believe in preserving heritage while looking ahead. Classic design elements should not be lost in favor of fashion. The twin-kidney BMW grille is all but history, the Mercedes grille is shrinking with each passing year, and the Maybach…. I don’t like retro designs, but I do favor tradition – I think I’m one of the few. These days, designers are paid small fortunes and want to leave their mark. I work to preserve the history behind a car. After all, history is what got them here.”

Paul and Alice’s son Boris Bracq manages an automotive restoration and maintenance shop focused on Paul’s works – and with Paul’s frequent consultation. Don’t be surprised if the Bracq name continues to circulate in automotive circles for years to come. Paul pats himself firmly on the chest: “I have many ideas left – and energy. I am a 25 year-old, but with 65 years’ experience!”

A true inspiration to us all.

More Information:

https://www.bracqheritage.com/

Carroserie Passion, 1991, Paul Bracq

Mercedes, les années Bracq, 1992, Pierre Ernst

Leave a comment